Behind the Data Scenes: Partnering to Build a Robust 211 Data Resource

by Adriann Gin, Hawai‘i Data Collaborative

Almost a year ago, shortly after the first case of coronavirus in Hawai‘i was confirmed, and residents were unsure how public health mitigation efforts to limit the spread would impact our local economy, our team focused on addressing the need for timely data in order to understand how households would be impacted and what support they would need. Traditionally, we relied upon robust data sources, such as the U.S. Census American Community Survey, to understand how households are faring. However, these types of data sources are delayed by one to two years, leaving decision makers navigating a crisis with very little data to understand how the situation for families was evolving on a month-to-month basis.

We had a hunch…

Looking at the Hawai‘i data landscape, Aloha United Way’s (AUW) 211 Helpline – Hawai‘i’s only free and confidential statewide community information and referral service connecting families in need to available resources and services – appeared to be a good place for us to start. AUW and HDC both recognized the potential for our organizations to align on more timely data for addressing household need, and AUW welcomed the partnership by allowing us to peer behind the curtain and gain a better understanding of the 211 system.

What we observed was a system containing several fragmented components – an unintegrated phone system; a resource database that required call operators to use an antiquated remote desktop connection; a separate database for call operators to capture caller data; no ability to capture website analytics; dashboard of caller data hosted on a separate platform. With a system this fragmented, fraught with unreliable data flows and prone to human error, the implications immediately raised data integrity concerns. Though our story started with an interest in 211 data as a timely data source, if the system supporting the data wasn’t reliable, then how reliable and useful would the data itself be? It was clear that the first challenge to address was upgrading the 211 system.

That was March 10th, 2020, the same day Governor Ige held a press conference on the coronavirus, with 211 largely displayed in the background.

Expanding the potential of AUW’s 211 helpline

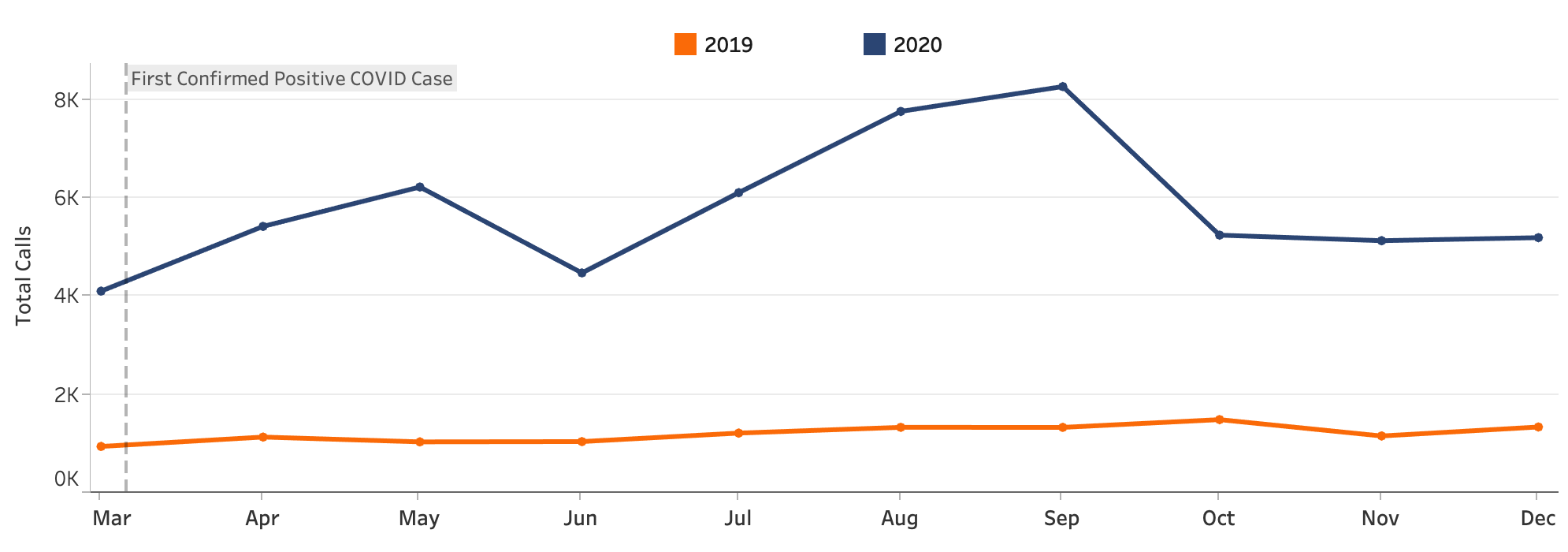

The number of calls 211 processed in March 2019 was 945; the number of calls 211 processed in March 2020 was 4,107, nearly a 335% increase from the previous year. In the weeks that followed, we worked closely with AUW to quickly connect them to resources that would support their capacity needs. The extraordinary increase in call volume from the previous year suggested an increase in first-time users of the 211 line, requiring an expansion of the 211 team to meet demand that has sustained throughout the pandemic (as the below graph demonstrates).

On April 23rd, 2020, the 211 system shutdown entirely, as inbound calls reached such unprecedented levels that the system could no longer support the onslaught. While the process of upgrading any kind of IT infrastructure can be long and disruptive to everyday operations, postponing the inevitable can have far-reaching consequences. Although the 211 system was eventually restored, AUW recognized the value of quality 211 data – how it could better inform their strategy and those of their partners – and was ready to take action in tackling its 211 data challenges.

Yes, the immediate need was a stable, reliable system that could support the increase in call volume from previous levels, but we also had an emerging need for insight, which made the data being collected from those calls even more critical. We needed this data to understand how vulnerable families were being affected, to what degree, in which areas of the state, etc., so decision makers could efficiently deploy resources to those who needed it most.

We also know that the devastating economic impact to households will have long-term consequences for years to come. How will policymakers, program administrators, and others working to meet community needs, know how best to allocate resources and design support services? What data is available to inform these decisions? And, once services and resources are allocated, what are the means to measure how effective those efforts were in meeting need? The likely answer to these questions is that we simply do not know, meaning that we need to develop new data sources to support decision makers.

As the primary resource for struggling households seeking support, we knew 211 data was uniquely positioned to fill this void; we just needed an upgrade to get there.

Setting the stage for data possibilities

Since we began supporting the work to upgrade the 211 system, the AUW team has been incredibly collaborative, welcoming us to walk alongside and gain extensive knowledge of the 211 system and program as a whole, while also creating space for us to share our knowledge that will set the stage for better data reporting. A more robust, flexible, and stable platform provides new opportunities to enhance 211 data by developing and refining the information flows to yield more useful insights.

At the moment, folks typically call 211 for assistance with a specific request in mind, such as the nearest food bank location, housing support to avoid eviction, childcare support, etc.; call operators quickly provide information for support services that can assist with the specific need reported by the caller. There is an opportunity here, though, to learn a little more about the individual, which can also lead to insights on communities more broadly. It’s possible that someone calling for employment support may also need assistance with rent and utilities, though the caller may not think to ask about support in those areas, leaving us with an incomplete understanding of the caller’s situation.

Instead, if all call operators were equipped with the same set of questions that yields a complete picture of each caller’s need(s), along with demographic data points such as race/ethnicity and household size[1], callers receive a more holistic experience to comprehensively address needs, and the dataset in aggregate provides a more accurate pulse of overall community need.

Take the statewide moratorium on residential evictions issued by Governor Ige in his COVID-19 emergency proclamation: it was set to expire February 14th, 2021, but was recently extended to an additional 60 days. This decision appears to have been driven by economic data from Hawai‘i’s Safe Travels Program (i.e., number of visitors) and state revenues. While these indicators can help us understand the state’s economic recovery at a high-level, we cannot reasonably assume that it informs how households are faring. If, instead, we could reference 211 data for the weeks leading up to February 14th and we see an increase in the number of callers seeking housing support, then we could more reasonably gather that households continue to be vulnerable in this area, and that interventions for housing assistance should continue, such as extending the moratorium.

We can imagine all sorts of questions to which 211 data can provide more insight, for example:

What are households in ‘Ewa struggling with the most?

Of those calling for housing assistance, are they calling for rent/mortgage assistance, shelter locations due to recent homelessness, mediation services to resolve landlord-tenant disputes, etc.?

In which zip codes should we set up food drives to reach the most households requiring food assistance?

Of those calling for utility assistance, which specific utilities are households struggling with the most, and in which areas of the state?

What were households struggling with the most in September 2020, and has that improved six months later?

In the coming months, we will be collaborating with AUW to build a dashboard that reports 211 data, updated weekly. Our hope is that by making this data publicly available, those who are working to support vulnerable households will be better equipped to make targeted, more responsive decisions that ultimately result in getting households the help they need. We encourage you to follow our progress as we continue to work on solutions for more timely data, and new approaches for collecting and analyzing data for addressing Hawai‘i’s pressing challenges.